Edie Fake

The Chicago artist talks queer history research snacking and living like a nomad in grease-powered buses.

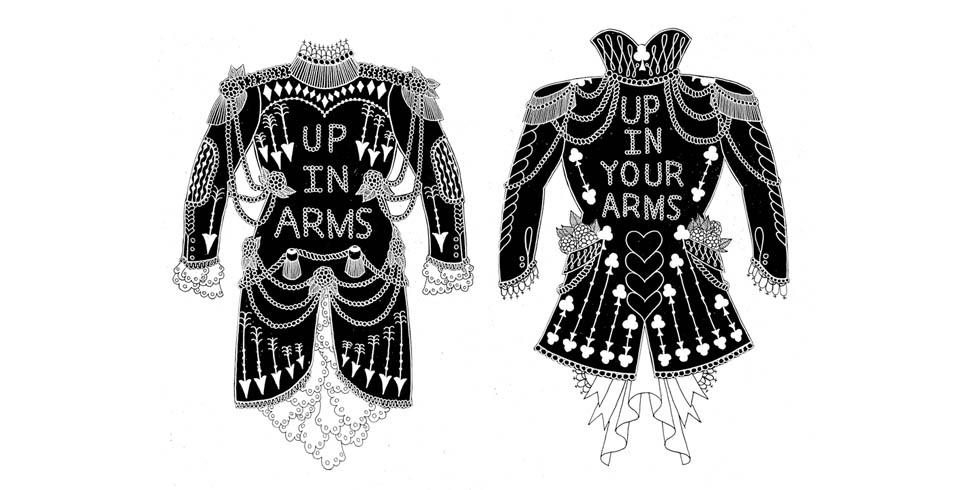

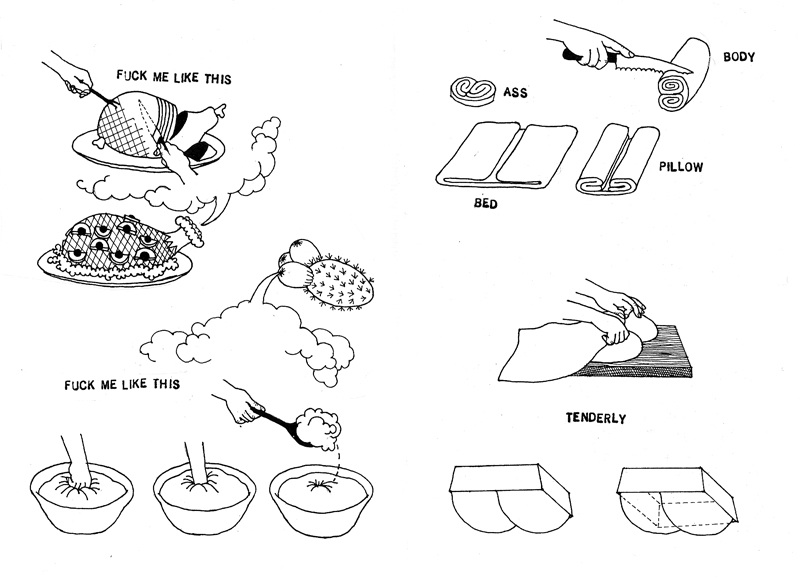

Just a small sample of the work Edie Fake has completed in the last few years gives you an idea of his recent bio: a food fetish zine called Foie Gras (based on some unintentionally lewd images in Joy of Cooking), a queer-mytho-log comic of Chicago named Gaylord Phoenix, and enough T-shirts and tattooed bodies to fill the grease-conversion school bus in which he toured a variety show called "Fingers" around the US.

His latest (and much more stationary) project, "Memory Palaces," recreates doors, entryways, and buildings, each significant to Chicago's queer history using geometric patterns, gouache, and ballpoint pen. We caught up with Fake on the phone from his Chicago studio.

You did a performance tour called “Fingers” in a converted vegetable oil bus. How did you find a bus like that?

When I got the bus it was living at this place called the Flower Shop in San Francisco, a lot of the folks there had done really innovative grease conversions on large vehicles. It’s a super squirrely, non-science science. A lot of kids who were part of that scene were buying old buses and doing amazing grease conversions. The person I bought the bus from did a really amazing switchover.

Then you had to scour for vegetable oil?

Yeah, sometimes it was legitimate and sometimes it was barely legal. I had a pair of coveralls and I was like, “This is my mechanic costume!” I’m really small of build and they were oversized, so I felt like a mechanic clown. And being like, “I have this bus I need to fill with your old grease, can I do it?” It was a total learning process. The first time I was on the bus and getting grease myself we found this dumpster with grease, but it was rancid desert grease. It was disgusting, it had dead fish in it. I was like, “Well I guess this will work...we’ll filter it a couple of times.” It was like headache-vomit. Learning that there’s more out there than just awfulness was important.

What kind of places were you guys performing? Were they proper venues or book stores and house shows?

It was a totally mixed bag. We did a show at the sculpture center in Queens, but also we’d play house shows and just spaces, a variety of spaces where experimenting with, where performing, could happen. There were nine people on the tour minimum, and we just had some big Google-clusterfuck in terms of organizing it. People were like, “I can get this city, and this city,” so it was through different peoples’ connections.

It’s interesting to take a show like that on the road. A lot of artists and authors just do hometown stuff and one-off shows. What was the impulse to do a proper tour?

Well, the fact that I lived on a bus. I crash landed in Baltimore for a season, which was winter, and not the smartest thing to do. But it was fun. By the time spring rolled around, I was like, “Oh my gosh, I live on a bus. I need to drive it.” The reason I lived on the bus was to be very nomadic and take everything with me, have that be a resource. It was because I had a bus: the vehicle was there and the will was there.

To change gears from the tour, you work at Quimby’s book store in Chicago during the day.

I do. I’m the comics sommelier.

Does that mean most of your studio time happens late at night?

Totally. I’m pretty nocturnal at this point. I usually run the late shift at the book store and do studio hours until about four or five every night.

Did you always work so late?

I’ve always leaned toward the lateness. I like how quiet it is at night. There are no distractions. I couldn’t like, go to the bakery. I could go get an all-night taco, but it’s not like during the day where I can be like, “I have to go run this errand, that’s more important than drawing this thing.” At night it’s like, “No, it’s time to do it.”

You've described screen printing as a healthy thing to do. That reminded me of your tattoo work in a way because they’re both kind of physically demanding mediums.

I think spiritually, being involved in the physical production transfers into the energy of the object but, also in terms of my commitment to making something, being totally hands-on feels very healthy to me. Sending something off to the printer still seems really weird as an idea. When it’s like, “But I could learn how to use this finicky equipment instead.” Whether I'm drawing or silk screening, it’s the long way around. I work very slow, that’s how I like it.

So how long have you been doing tattoos?

I don’t tattoo anymore. I still design tattoos for people. I did a year and half apprenticeship, and then another little while doing tattoos in San Francisco. In terms of making me commit to drawing, it really did the trick. You have to draw things you wouldn’t normally. It was like boot camp or something. Putting them on people was casual, but it was also, like, blood ceremony. Like a casual blood ceremony!

How much back and forth is there with the people you’re tattooing?

Sometimes the person is very involved in the process, sometimes people are just like, “Fill in everything black, I’m going to sit back and take the pain.” I was lucky to have a lot of scrappy friends who were like, “Totally do an apprentice tattoo on me.”

I developed a design sense drawing specific things. People would be like, “Draw a cat...but how you draw it.” Then I draw a cat and they’re like, “No, more like how you draw it!”

How do you approach designing something wearable like a T-shirt or a tattoo as opposed to drawing a comic?

I think tattooing is a special kind of illustration work and design work. And you have to think about the element of a gift, and developing something that’s appropriate to a cause outside of yourself. So for tattoos I would think about it like choosing the perfect gift for someone.

How did you first get involved with Secret Acres?

It’s a really clowny story. They had contacted me when they were first starting their press, but I was living in New York and working on the west coast at the time in this film job. So they sent me a letter that I didn’t get because I hadn’t been home in four months. Then I ran into them at a comics show, and I still didn’t know they had contacted me, and they casually asked me if I’d ever been interested in publishing. I thought they were fans of the zine, I didn’t think they had any interest. When I got back to New York I got their letter, and we had a dinner meeting and it was like, “Oh! You guys are the guys from San Francisco who were really cute!” It kind of almost didn’t happen.

I’m curious about your research process. A lot of your work is about imagined histories and actual historical events. Where do you start?

I guess it’s a mix of personal sources and things that I read up on. For this last series of drawings I was reading up on gay history, almost in a casual way because I didn’t know a lot about the queer history in Chicago. So any time a name really struck me I would make a note of it to delve deeper into that realm. Through the project I came to realize I’m not a great researcher: I’m a research snacker. It’s the potential of the past I’m after, not the nostalgia for it. It’s a combination of knowing that something happened, and then “What if it was realized like this?”

Your website has this unmarked stream of images that you pulled from zines that could be hard to track down now. The site reads like an auxiliary project to the zines themselves. How did you choose which images to digitize and which to keep in the printed zines?

My website hasn’t been touched in a little while, but I think about what looks good cascading after things. The website was me half-assedly teaching myselfing HTML. I was like, “You know what looks best, the prettiest images from the zines on a white background.” My Tumblr is a wet dream for me. I don’t post things that often, but that is my preferred way of looking at the Internet. Beautiful images just endlessly cascading.